June 17th, 1940.

I arrived in Hereford to begin life in the army. As I walked through the main gates of the barracks, news came through that France had capitulated. Not a good start.

This was an artillery regiment that we had been sent to for military training. After the first two weeks of intensive workout, we were given two days leave. I was so tired, I slept most of it. I thought I was fit, but playing tennis occasionally after work was not enough to prepare for this onslaught. After another two weeks of this program, I quickly found out that I was not going to be the soldier my Father was. He was a crackshot. I was mediocre. In all other aspects I fell short of his example. The army was going to work hard to make a soldier out of me. They did that, but whether the result was what they arrived at begs the question.

From Hereford we were sent to Dartford, Kent. At the Tech. College there we received a basic engineering course. It was while there that the Battle of Britain began. The air attacks began and never ceased.

From Dartford to Acton (another London suburb) for more Tech. Training, 8 hrs Tech. training and 3 hrs military per day. During this time the air raids continued unabated, day and night.

While at Acton we got a weekend leave every month. A Welshman I teamed up with knew of the Toch H Club. They were housed in that building opposite Big Ben. We went there by the underground rail from Acton, and spent a pleasant two days at the very centre. By now the underground rail stations were used for air raid shelters and were packed with people every night.

Xmas 1940 I got 5 days leave. Those days disappeared all too quickly. When I said goodbye to my Mother and Father, I had no idea that this would be the last time I would see them alive.

The next few weeks was spent with more training and lectures in Stirling. One lecture in Stirling Castle, given by a Uni. Professor from Edinburgh, had a significance that did not strike me at the time (but did well and truly later). It was titled JAPAN WITH THE LID OFF. It was this reference that they behaved like cruel, grotesque children.

From Stirling to Nottingham to be fitted out for overseas. The U Boats were by now sinking ships at will almost, and many convoys leaving our shores were attacked. This resulted in having to increase security. The camp commander said he would even muffle our boots when we marched to the station. From Nottingham by rail to Greenoch, where we got off the train and marched to the dockside and the doors were closed behind us in the steel fencing. This was it. We were leaving Britain and could not tell our parents, due to tight security. From the dockside we were taken out to the liner Strathmore lying at anchor with all the other ships in the bay. Close to midnight I heard the steady beat of the propellers and we were under way. At dawn there was no sign of land. We were on a westerly course in the normal zig zag fashion, out front the battleship Nelson (very comforting), cruisers and destroyers darting around like guard dogs. That awful sinking feeling crept over me. England far behind and my family unaware of my whereabouts.

First port of call, Freetown. No going ashore there. Then down the coast to Capetown, where we arrived without being attacked.

We were allowed ashore in Capetown, but only just. Some weeks earlier, the Australians bound for the Middle East had been ashore and almost wrecked the place. They took charge of the city, e.g. stopping German made cars and telling the occupants what they thought of them, etc.

This gallant bunch of true blue diggers were the troops that P.M. Curtin fought hard with Churchill, to have returned to Australia when he became aware of the possible threat from Japan. These tough, battle-hardened men took the brunt of the later war in New Guinea.

During that few weeks that we were in Singapore, before the Japs bombed the City, these Australians passed through Singapore on their way back to Australia. They were different altogether from the disciplined Australian 8th Division we already knew.

A humorous incident occurred one day when Alec and I were having a haircut. Covered up with a sheet in the barber’s chair, all that was visible was our brown boots. Normally the Brits had black boots, but being attached to the Indian Army, we were issued brown boots similar to the Aussies. Four of these Aussies came in for a haircut, and the front runner came to me and said, in that broad Aussie accent, “G’day, Dig, how’s it gowen here”. I lifted the sheet and said that I was English, showing him the insignia. He turned to his mates and said, “This bloke’s a Pom”. His mates retorted, “Ah well, we won’t hold that against him”.

After two days in Capetown we set sail for Bombay. On this leg of the journey the escort was reduced to one destroyer. From Greenock in Scotland to Capetown we had the battleship Nelson and other warships as an escort. Not one chink of light was ever allowed to show at night from any ship in the convoy.

After disembarkation in Bombay we spent a week in the barracks. From Bombay to Rawalpindi by rail. In Rawalpindi we were promoted to sergeant and promptly attached to the Indian Army, from there split up into small groups. Six of us were posted to Chinkiawi high up in the Himalayas. There under canvas (very primitive) we were part of a workshop unit servicing an artillery regiment. Our job was to keep tanks, guns, and motor vehicles in working order. Two officers and six of us were English, the rest of the company Indian.

Suffered my first bout of dysentery in these conditions and was sent to Kashmir to recuperate. Getting there on my own was a story in itself. Once there, 7500 ft up the Himalaya mountains had an aura of beauty. The silence and cool climate helped me to regain my strength.

On my return I was sent back to Bombay on a four weeks course on my own. When the course ended my return warrant was delayed. (This was to change the direction of my life). When I eventually got going on my return to the company I got off the train in Lahore for a stretch and a walk along the platform. There I met two of my colleagues who told me that I had been posted with them. I left the train and went with them. I should have continued on back to base. A day later, when I had not returned, they sent a replacement and subsequently I returned to the company. After the war I found out that they had been posted to the Middle East and never heard a shot fired in anger. Some weeks later I was posted to Peshawar where I joined the 46 Mobile W.S. company. After some more training and exciting adventures near the Khyber Pass, we set off by rail to Madras. A six day journey. From Madras to Singapore by steamer (no escort). Arrived Singapore November 11th, 1941.

Before Singapore the ship called in to the Penang Island on the NW coast of Malaya. Two days there made us think the war was over. It is a real holiday resort, and I felt guilty because the war was far from over and my thoughts were constantly back in England with my family.

In Singapore we joined up with the rest of the company at the Alexander Ordnance Depot. Now at full strength, the company had a Major C.O., four Captains, 3 Lieutenants, 3 Warrant Officers, and 6 sergeants. Alec Underwood, who I first met in Peshawar, and I became firm friends and this real friendship continued until 1989 when, regrettably, Alec died.

Life in Singapore was unaffected by the war raging on the other side of the world. No blackout, no restrictions of any kind. All this came to an abrupt end early (about 1 am) on December 8th, when Japanese bombers dropped bombs on the city. The regular army servicemen at the Depot where we were stationed thought it was a practice. Two of us who had already experienced the London blitz convinced them otherwise, and on the second wave of bombs they soon dived for cover. Now we were really at war. Within two days the 11th Indian Division were ordered to move north. Our company joined the convoy at 7 am on the 12th December. When we crossed the causeway into Johore, all the non-commissioned officers were detailed to keep the convoy moving, which meant moving up and down on our motor cycles, making sure all the vehicles in our company were on track.

I was detailed at this time to go to the head of the Division convoy to report to the Divisional commander that 46 Mobile W.S. company was in the convoy at the rear. The staff car he was in would have a black flag with a white cross draped across the rear window, I was told. As I proceeded north, overtaking dozens of vehicles which were sometimes in groups, and at other times long gaps before seeing others. As I passed each staff car I looked for this black flag. After a long spell without sighting a single vehicle and almost out of petrol, I did an about‑turn. The convoy was halted when I made contact again and the commander was sitting on the side of the road taking stock of the situation. I gave my report to him, and after filling up the tank with petrol, and a welcome drink, set forth to rejoin my mates. Long spells at the wheel began to take toll and quite a few accidents occurred, and as a consequence we NCOs on motor cycles spent the first 36 hrs of the campaign without sleep.

I forgot to mention that the black flag had slipped down unnoticed, hence my not seeing it. The commander apologised to me personally. The remarkable thing was that the 25 mild-long convoy.- (A WHOLE DIVISION) was never attacked from the air while going north. On the retreat south it was different. We had to continually find tree cover, rubber or jungle, to continue our work keeping tanks, guns and vehicles in working order for the whole artillery battalion we were attached to. This was to prove hazardous at times. Being last to leave the area, we were often cut off by the advancing Japanese. Through it all we lost only one officer. Killed in action. Alec, my mate, was hospitalised with a broken leg and did not join us until we had been in Changi for two months.

The Japanese continued to push us back until eventually we crossed the Causeway back onto the island of Singapore. Blowing up the Causeway was a futile attempt to stop the advance. They landed on the NW coast in a swamp area that surprised our leaders. We continued to find cover from the continuous air attacks. Our airforce was non-existent by then. In the last three days we were camped on an open park within sight of Raffles Hotel, and suffered bombing strafing from low flying aircraft and artillery fire. One by one the antiaircraft guns that gave us some protection were knocked out. We were completely surrounded. The next move was down to the dockside on the final day. The cease-fire came in the late afternoon, and we heard the news from London on the radio. I remember feeling cut off from life as I had known it. All I possessed was the clothes I was wearing, shorts and shirt. All my kit was burned in a fire, treasured things like 21st birthday presents, etc. What had we to look forward to? Captain Carless gave us a brief outline, i.e. two meals a day, if you are lucky. That night he and two of us attempted to escape, but failed.

Before moving to Changi we were still camped in a large storehouse on the dockside. An Anglo Indian warrant officer asked me to accompany him to have a look round the city. I sought permission from our commanding officer before departure. On the outskirts of the city we came across streets lined with abandoned cars. We picked on an open tourer of classic make and soon started it, even though the key had been thrown away. We toured the area without being challenged, and witnessed some gruesome sights, i.e. severed heads stuck on poles to warn potential looters what fate was in store for them. After touring round in this fabulous car, visiting the park where we were subjected to such incredible attack from the air, artillery and mortar fire unchallenged, my thoughts were to keep going north and take our chance. The causeway had been blown up, of course, so this was an impossible dream. We were prisoners on a small island.

Serlerang Barracks before the unconditional surrender

The following day we were marched into Changi on the NE coast of Singapore. Apart from the lack of food, life as a P.O.W. in Changi was to prove the best of P.O.W. existence. Our leaders had negotiated conditions where, apart from daily roll call, we were inside our own compound without direct contact with our captors. If we wanted to visit other Divisions, e.g. the Australians who were across the road to us, there were what we called ferry times. There were four of these a day and while crossing, the party carried the flag of truce. There were the usual duties to be carried out and in spare time (a privilege after leaving Changi was a rare event) there were many activities organised. Language study, Spanish, French, Astronomy classes, etc., concerts, and even some sport, if you were fit enough. After eleven months of this, it came to an abrupt end, when we were drafted to join other working parties that had gone before us to the infamous railway between Bangkok and Moulmein.

To back-track to Changi, I must mention a very dangerous situation that occurred there. A paper was circulated requesting all of us to sign, saying that we would not attempt to escape. To a man no one signed, resulting in swift and brutal action. The whole of Changi personnel were moved to Selarang Barracks square. Selarang had housed a single battalion before the war. Imagine the scene with thousands of us, Australian and British, crammed into this small area. After three days it was decided (especially after the threat of bringing the sick from the hospital among us), that we would sign under duress. An outbreak of disease would have spread so quickly under the conditions, resulting in much loss of life. We signed, and were told it would be recorded officially by our commanders that it was under duress, which means, it was not valid under law. We were still free to attempt escape. The journey north was in cattle trucks with little ventilation, 35 to a truck. No room to lie down, in unbearable heat. After 5 days of this we off-loaded at Nong Pladuk. To backtrack on Selarang, I forgot something that I feel strongly about, and should not be forgotten, is that the Sikh soldiers deserted and went with the enemy. These deserters were our guards while in Selarang. I personally regard them as the lowest of the low. Some have spoken in their defence. I never will.

At Nong Pladuk we camped in the most abominable circumstances one could imagine. No latrines, sewage everywhere, and the area was flooded to a depth of approximately 9″. This was a good start. After two days of this we were loaded on to the back of a truck and driven (again no room to sit) up the so-called road cut through the jungle by previous working parties. The first stop late at night was high up in the hills, which was the base camp of those who had cut this track. The next day, after a freezing cold night, I witnessed something that I will never forget. This battalion of men, including their officers, were a spent force. To look into their eyes was to me one of the saddest experiences of my life. There was no spark there. Everyone had a vacant look, as though their spirit had been broken. They were like living corpses. I will never forget, and hope to God I never see this again. This was untouched jungle, and the wildlife was plentiful. Wi1d cat were very prolific, and so large. Eventually this cruel journey came to a stop at Kinsaiyok where the main party was to spend the next 6 months. 14 of us were sent further up the line which followed the line of the River Kwai, and camped at a place close to the Burma border, where we eventually linked up with the line coming from Burma.

The next 6 months were a battle against disease, cholera, dysentery, beriberi, etc. and our captors. There were 15 of them, 14 of us. Against my better judgement I agreed with Alec that we declare our trades before leaving for this job. I strongly believe in the safety of numbers. Our job was maintain the vehicles and river boats bringing supplies to this remote area. Alec was given a job on the lathes in a motorised workshop vehicle, and I in the welding shop. The others were on repairs to truck maintenance. I foolishly, at first, sabotaged every job I did on the repairs, and suffered as a result. Some of the beatings were particularly brutal, and almost lost my left eye in one, after being hit with an iron bar.

So life went on here, sapping our strength. Every one of us should have been in hospital with any one of the aforementioned diseases. Malaria took its toll and we were given time in bed while the fever lasted. The line was complete.

From the Three Pagoda Pass we returned to Kinsaiyok and re-joined the main body. During our term at the border it rained without stopping for 3 months and the river, which was fast-flowing and large, became a raging torrent. Unforgettable. I was first to leave for Kinsaiyok by the river boat with 2 Japanese and the Thai crew. I could fill a book on that adventure alone.

From Kinsaiyok, slowly back from camp to camp, kept working on repairs to the line and bridges, until eventually reaching Kanchanaburi. The sick and wounded, and that was all of us, had a few weeks to recuperate before the next onslaught. The next step was that 5-day rail journey previously described, back to Singapore. On arrival there, we were sent to Havelock Road camp, near the city. We never returned to Changi.

Survival in such circumstances is a result of – Hope, faith, and keeping a sense of humour. Camaraderie among your mates played a most important part, and witness to such remarkable genius – e.g. Weary Dunlop saving lives with such skill, as a doctor and surgeon. Then there was continual rumour that Germany was finished, which kept one pumped up for days. Personally, I lost (or almost) my sense of humour 3 times. First, shortly after entering Changi, I got dengue fever and just lay there in deep depression and frustration at being out of the battle. A sense of guilt, perhaps, at not being in a position to do more in the war effort.

Then in Hintock, a transition camp on the way back down the line after its completion. I had been working on a bridge up to my waist in water, with a temperature of 103°. It was too much, and I collapsed, and after 3 days of lying in this dark hospital hut, slowly dying, my sense of humour almost gone, I had a visit from Alec (who had, as often happened, been weeks on another job. and we had lost contact) found me. Shocked at the sight of me, he took a tough line and said, “If you are not on your feet by the time I get back tomorrow, I’ll drag you out”. The next morning I did get up, and made for the river to wash. The river was only 30 yards from the hut, but took me over an hour to get there and back. When Alec returned, he brought me a pomelo, which he had purloined. (A pomelo is very like a grapefruit). I sucked on this, which was the first thing to pass my lips in 3 days. Slowly I regained strength, and regained my sense of humour. Back in the fold.

To backtrack again to Changi. I mentioned previously all the activities we could participate in among all that wealth of talent. One officer had managed to smuggle in a wind‑up gramophone and a large collection of classical records, about which he was so knowledgeable. While camped close to him, we never missed his delightful programs, which were held at night under the stars. Those brilliant starlit nights were such a pleasant memory. At this point on the earth you can see the southern cross and the plough in the sky at the same time.

To mention a most important fact at this stage is, I think, appropriate. Alec saved my life on many occasions. His courage and daring were astounding. With fear and trepidation I stuck with him on these adventures. Memories come flooding back to me ‑ in the wind, in music, in the stillness of the night,‑ and down the evolving years. These are not my words but those of Charles Dickens about his childhood. In my twilight years I think you will forgive this bit of plagiarism. I love the words Dickens used, and surely they fit. As I look back and marvel at my survival, and be forever grateful for the inspiration I received from Alec Underwood. Also the fact that no matter how desperate the situation became, there would always be that genius among the party, whose wit and humour would break the tension, and after all, the best cure for all ills is that good genuine belly laugh.

Another interesting factor of the Changi episode was the ingenuity shown in overcoming the lack of modern conveniences. No electricity, of course. Our means of transport were trucks, stripped of all but wheels, chassis, and steering wheel. We had ropes out front to pull the load uphill, which made a scene like ancient Egypt. Going downhill we would all jump aboard, which unfortunately sometimes led to a horrific accident due to the failure of the ingenious brake system invented by a few of the blokes. There have been some artists.’ impressions of such scenes. . I think they might be in the War Memorial. I could go on and on with little anecdotes.

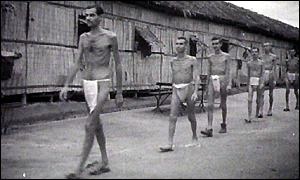

British POWs on the ‘Death Railway’ in 1943

The third phase of P.O.W. began. This was May ’44. Behind us were the rubber plantations of Malaya, and further behind the Thai Jungle, infamous railway and the graves of thousands of our gallant mates. From Havelock Road camp, where rats had outnumbered us two to one, we marched to the quayside where a few ships lay alongside and more than a dozen anchored in the roads. P.O.W. travel is not for the impatient, and there we waited for the next move.

Upon a voyage across uncertain seas To ports unknown, in strange unknown countries. No hope of fortune theirs! No hope of fame! No hope of quick release from prison’s scheme.

“Slaves of the Samurai”

W.S. Kent Hughes Minister of Interior Menzies’ Govt

19.11.97 The Journey to Japan

Doctor Bras

Before proceeding on a brief description of this last leg of P.O.W. life, I will recall one of those coincidences that occur from time to time. Last night the phone rang, and it was Olga Sinclair, who lives in Mount Eliza, Victoria. Olga and Les (who died recently) were friends from school days. They came to live in Australia after Les retired, to join up with daughter Kate and family, and son David and family, who had made the journey here earlier. After the war I spent such pleasant weeks as a guest of Olga and Les at their home in Cheshire, before departing for Australia. Olga rang to tell me that Les Horton, a school friend. who lives in Cheshire. and had worked with Les, had sent her a newspaper cutting concerning Gen. Phillip Toosey, who had been a neighbour of Olga and Les in Cheshire.

Gen. Toosey, who died in 1977, never spoke much about P.O.W. life, apparently made some tapes for BBC on his experience. The film, Bridge over the River Kwai, was based on his story. Olga recalled that I had spent an afternoon with Gen. Toosey after she had told him of my being also a Japanese P.O.W. Apart from saying that we had shared the experience of the infamous railway, our conversation centred on the future, and I recall that when I said that I was contemplating going to Australia, his response was, “Is that what you really want to do?”. This made me think, because by now the spring sunshine had warmed the land, and all those smells and beauty of the countryside were evident. These were the dreams and smells I had longed for over the past five years. Also by now, I had regained my strength enough to play tennis at the club with Olga and Les. At night we talked of the happy times we had before the war, that joy and happiness which is the right of all people, but can be so cruelly interrupted by the tragedy of war.

I told Olga of the coincidence of her phone call when I had just started to write of my experience. In our neighbourhood alone, that cruel war accounted for at least three of our close friends: Howard Hume, sunk in the Atlantic by a German U Boat; Kenneth Steel, shot down over the English Channel in his Spitfire; Douglas Potts, shot down in his Lancaster bomber over Germany. They remain forever in our thoughts, and the pleasure they gave to us being their friends. To use my Father’s often used phrase, “The world is a lot poorer at their passing”.

Journey by Ship to Japan

At long last we were ordered to board a lighter which had come alongside the quay, and were taken by it out to the ship. It was a long passage, and there was a fair swell running. When alongside the ship, we had to jump ten at a time on to the freighter’s deck, picking our moment as the lighter rose and fell. Since this was done complete with kit (such as it was) it was a miracle that no one was hurt. I consider it as a miracle, because in our weakened condition, to perform this feat that would have taxed us, even at the peak of our training.

The ship was the Hioki Maru, a coal burner of about 4,000 tons. She was already overloaded, with the plimsoll line visible well below the water. The cargo, our officer found out, was scrap metal, rubber, and tin, to assist the war effort back in Nippon.

On the first morning after getting underway, I awoke after spending an uncomfortable night jammed up against winch on the forward deck (which was our allotted space for the entire voyage), and tried to stand up to stretch my aching limbs. It was then I noticed the first sign of a new ailment for me, Oedema. My legs had swollen, and when I pressed my thumb (the standard test) into my ankle, the thumb-print remained. Not a good start on this long voyage, because it gradually got worse as the weeks went by.

The toilet arrangements were to prove another athletic challenge of immense proportions, particularly in heavy weather. It consisted of a wooden platform slung at both sides of the deck with the middle plank missing. At least there was running water – the whole of the Pacific Ocean. These were the conditions for the next few weeks. The only thing going for it was that we had fresh air, stuck there on the deck, exposed to all the elements. It did not take much of a swell to bury us under the waves as they broke over the forecastle when the vessel ploughed into heavy seas. This fresh air was to come to an abrupt end when we reached the Philippines. We were forced into the “Black Hole”.

This Black Hole was an area under the bridge, which ran the full breadth of the ship, inside two tiers of shelving about 3 ft apart.. It was upon these that half were herded when the doors were opened to admit us. Those in front hung back because of the sudden release of searing hot air that came from the black hole. To answer this hesitation the guards let loose with rifle butts and crammed us in. Once in there, the doors were shut and the only light was two dim blue lights. Due to the extreme heat and lack of air a few quickly passed out, and we hammered on the door to get relief. The doors were opened because the guards thought it was a pending mutiny, and made a frenzied attack on those nearest. Our officers and the doctor explained, with great difficulty, the reason for the door hammering.

An uneasy calm was restored and those badly affected were let out to be attended by the doctor, who also pleaded on behalf of the rest of us to leave the doors ajar and let some air into this airless chamber. The reason for all this was so that we would not witness the track the convoy was taking into Manila through the minefield, and to see the coastal defence around the Corregidor. Alec said to me, “For God’s sake, even if we were to plot the course, how in God’s name could we possibly make use of the information?”. The madness of our captors never failed to astound us, and it just continued. Those words I heard from a lecture at Stirling Castle while stationed there. A lecture by an Edinburgh professor called ‘Japan with the Lid off’. He called the Japanese ‘Cruel and grotesque children How true those words were proving to be.

Finally we heard the anchor rattle out and the doors were fully opened. The City of Manila was about half a mile to our east, and the sea was calm and the sun beat down without any tempering breath of wind. Very hot indeed, but these extremes were now commonplace, and had to be endured with courage and humour to support each other.

After taking on the necessary supplies. we got under way and were rifle-butted back into the Black Hole until the ship was clear of the coast. We now had five more ships in the convoy for the next leg of the journey. Soon the weather deteriorated, and the sea sluiced across the deck two or three feet deep, with such force that it was hard avoiding being swept overboard. The weather was still rough, when one afternoon the convoy was attacked, presumably by American submarines. The ships scattered, and as they did so, came under fire from their own escort vessels. A small destroyer we saw dropping depth charges, and in the confusion, the handful of Korean guards panicked and had to be disciplined by the Japanese. This was the usual face slapping technique.

Right from the start the favoured word of command for the Nippon was “Speedo” screamed at you by these ill-tempered crazed lunatics, especially on that railway. It continued right to the end, and at this moment, with legs swollen with Oedema, it was frightening. There was no justice.

The next day we sailed into the most southerly port of Taiwan (JAP), was Formosa (Portuguese), meaning beautiful. There were the masts of a few sunken ships to be seen. Two light A.A. guns were installed at the stern, which was strange, since we were now within reach of Japan itself. After the war we learnt of the American carriers sending planes to bomb convoys. On June 24th, we passed close to some islands and later we caught sight of Japan in the late evening. About 11 pm the sky was lit up with a brilliant flash and a loud explosion, which shook the Hioki Maruy the large ship to the right of us, carrying P.O.W.s from Java (they were all killed). Two more ships and tanker were also hit.

I was feeling so ill and depressed that I prayed that we would be next. The American submarine had done the job and fled. I learnt after the war that the submarine surfaced a day or so later and picked up some Australian survivors. The Koreans again went wild and were calmed down in the usual way by the Nippon, or the Nips, as we nicknamed them. At one stage after the attack it was full-steam ahead in the opposite direction to what we had been sailing. Before the attack the moon, which was full at the time, was on our right. After the attack it was on our left. I fell to sleep with exhaustion.

The next morning we were warned to be most punctilious about saluting and bowing because the Nips were extremely touchy after the bitter blows of the previous night.

We entered Mopi in the late afternoon, 26th June. It was like an English summer’s day. The following day we were marched ashore and counted and recounted ad nauseum. We noticed some bomb damage on the dockside and the civilian population did not look at all friendly.

Eventually, we were bundled onto a train. The doors were locked and blinds drawn. Whenever we stopped (which was frequently), we were looked over by the dreaded Kempei-tai (Jap. military police), much feared by all, including our Jap. guards.

It was nearly midnight when we halted. Once off the train in the pitch blackness. We could see lots of little lights bobbing up and down in the distance. When they came closer we could see they were civilians wearing miners helmets with lamps secured to them. Alec said to me, “This is it. We are going to become cogs in their infernal war machine”. We were tired and very apprehensive.

After more counting we were marched to Camp 17 of the Fukuoka Group of P.O.W. Groups Omuta which is about 40 miles east of Nagasaki. This was our last camp as P.O.W.s, 200 tired, weary Englishmen.

Camp 17 of the Fukuoka Group

Before getting a much needed meal and rest, we were kept for another two hours on the floodlit parade ground by the pompous ass of a camp commander telling us the rules and regulations of this wonderful camp. This was our introduction into civilisation?? after the jungle camps where conditions were primitive. Here we were fenced in by an electrified fence, similar to German P.O.W. camps.

The accommodation was long huts with a corridor running the full length and rooms off to the right, where you stepped up eighteen inches onto a flat surface of straw matting. That is where we slept. The lights in there were never extinguished.

Constant harassment by petty regulations. The cold in winter. The back‑breaking work at the zinc factory (description later), and the poisoned atmosphere (created by the American collaborators) all combined to rasp the nerves and infect us with near‑despair for the next thirteen months at Camp 17 Omuta.

After a few hours rest in our new quarters, and the introduction to one of the most dangerous regulations (we each were given a number mine 940 – and tag with the number on it) we were taken five kilometres to the zinc factory where we would work.

Because of the pressure on manpower caused by Jap. losses in the war zone, men were taken from these industries and we were to take their place. We watched as they performed the task we would start doing the next day. It involved milking the furnace of the moulting zinc which was held in the banks of retorts (long ceramic oval cylinders), then recharging these retorts with the raw zinc, which we shovelled in and sealed off to melt overnight, and so, on the following day, start the process over again. It was described aptly by Alec as “Dante’s Inferno”. The searing heat in front of these banks of retorts was such that after a few minutes at the job we had to race out and jump into a tank of cold water. (This we had witnessed while the Jap. civilians were performing the task.) This job would have been considered extremely hard work for fit young men. But to have to do it on rations, according to Dr Bras, that were barely enough to sustain life, and the already great loss of weight through illness, etc. was …

More often than not, three or four of these retorts would burn out and have to be replaced. The replacement of these monstrous white hot retorts was performed by the civilian overseer withdrawing them from the furnace and two of us at each end of a long bar would catch the end as it dropped down, then quickly turn and head for a spot in the concrete floor and flip the thing down a thirty foot drop to the floor below. So often it was hard to keep your balance after this exercise and not follow the damn thing down there.

This was to be the pattern of life from now on. On return to Camp 17 we were goose‑stepped in front of the guardhouse, counted, re‑counted, then dismissed to line up for the third meagre ration of that measured bowl of rice and soup? It was in this large mess room that we were to witness one of the evils of the American Mafia. Let me say at this point, that there is no judgement on the American nation, or most of the Americans in the camp. It was this evil crowd of collaborators that poisoned the atmosphere. We could not believe our ears when we heard these loud voices screaming out, “Rice and soup on the 26th of whatever month (sometime in the future) for rice now.” This bartering was just one of the new evils that caused so much trouble. Previously when you were too ill to eat, you automatically gave your ration to a colleague with no thought of compensation. Now this!!

The cotton drill uniform (JAP ISSUE) was no protection against the cold of winter, and always we had cold wet feet in those strange rubber boots with the separated big toe. After the searing heat of the zinc furnaces, the long cold march back to camp was instrumental in many cases, of pneumonia, with a consequent death rate of sometimes four men a day.

‘To what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul’.

The Dreaded TAG System

As aforementioned, we all had numbers and these tags were issued with our number on them. Outside each cubicle was fixed a board with nails and marked with each occupant’s number. JAP characters placed against each set of nails listed the various places where each P.O.W. could be. Work out of Camp, Work in Camp, Toilets, Mess Hall etc. Every time you left the cubicle the tag had to be correctly placed. If in the cubicle, you placed it on the cubicle nail. The guards inspected this board at odd times throughout the day. To forget this irritating order meant that you would have to report to the guardhouse to retrieve the incorrectly placed tag. A dash to the toilets, for example, would often leave the tag incorrect. While at the guard room, the victim would be subjected to the most humiliating and cruel punishment. Stood to attention through two or three changes of guard; rifle butted, kicked, punched in the face, and so on.

One or two, depending on the sadistic nature of the guards, were beaten unconscious, sprayed with ice cold water, and thrown into a cell naked. Only once did I forget, and when I discovered my tag had gone, I was, to put it mildly, petrified. When I reported to the guardroom (and this was after the usual day’s work at the factory) I was stood to attention in the freezing cold until roll call the following morning, when I had to front up for another day at that factory furnace. Each change of guard produced the bashing mentioned. My mouth was bleeding badly, and I had to be treated by Dr Bras before departing for another day’s work.

These are just a few of the daily trials in life at Camp 17. To add to my discomfort, my mouth became ulcerated after the guardroom incident. Eating even rice was painful. Rumours were rife at this juncture, e.g. McArthur’s success in the Pacific, and the opening of the Second Front in France. All this helped to keep up the spirits. Then in June, the bombing of Japan started in earnest, and we witnessed wave after wave of bombers at a very high altitude.

In late July I became ill with dysentery and Oedema. My legs swelled up in an alarming fashion. I was admitted to the intensive care hut. (A product of fear on their part to impress any Red Cross visit.) I came under the care of Dr Bras, a well educated gentleman, who was a tower of strength. So many times he saved the very ill from being sent to work. For such courage he suffered.

The lad in the bed opposite was from Northumberland, and he brightened up the ward with humour spoken in the great Geordie accent. He was suffering from the same disease as I was, and during the night succumbed to drinking water to satisfy the terrible thirst that oedema produced. They found him dead at dawn. Dr Bras was visibly upset. He had tried so hard to keep us alive and the Geordie lad was a favourite with us all.

From intensive care, I was moved to Another hut, after the water left my body in the normal manner. A new menace was body lice return, after being free for only a month. It was while I was in this new abode that the American planes came in at night and dropped incendiary bombs. I heard this droning overhead, and then bombs dropped all along the space between the beds. Five, at least, dropped into the hut and, of course, in no time at all, the hut, like all construction in the town of Omuta, being a wooden construction, was ablaze. I was slow to react, until I realised that some Nazi bombs dropped on London, burnt for a while, then exploded. These fortunately did not. Half the Camp was burnt down in this raid. When daylight came, we could see the zinc factory, which was five kilometres away. All the buildings between the camp and the factory were burnt to the ground. The factory, being concrete, was all that was left standing. We could see a long trail of Japanese civilians walking in file out of the area.

On August 9th, the atom bomb. dropped on Nagasaki. We felt the earth tremor, but the general opinion was that it was just another quake, so common in this part of the world. On the 15th August most of the guards left the camp, and a holiday was declared. We were told that it was to celebrate their dead enemies. Of course, it was the end, but we did not know this until two weeks later, when the B29 bombers came over unopposed, flying quite low. The bomb flaps opened and out came large platforms on huge parachutes. These dropped on or near the camp. It was supplies of food and clothing, and a message to inform us of the end of the war and to stay where we were, and that we would eventually be picked up and taken home. One of those sad tales was the result of this supply drop. Some of the parachutes failed to open and resulted in the death of two American P.O.W. So close to freedom.

On September 15th, we were assembled and taken by train to Nagasaki. I was strong enough to look out at the devastation. At least five kilometres from the centre of the bomb blast we passed huge trees completely uprooted by the blast. I have often described the centre as being like rubble laid down by a builder, before pouring concrete. Near the dockside where we got off the train, there were the remains of destroyed gas tanks, an unbelievable mass of twisted steel framework, an example of extreme violence. Once off the train, medical care was immediate. With relief, I was sponged down with a white substance, which killed and removed the hundreds of body lice, a quick cure to what was previously a drawn‑out procedure. Modern technology. After a beautiful hot shower, and one more check, it was on to the hospital ship tied up at the wharf, and into bed between clean white sheets. From Hell to Heaven.

Nagasaki harbour was full of American battleships, but one that caught my attention over to my right was the one flying the Union Jack. Only one, but such a wonderful sight that brought a lump to my throat. I really never thought I would ever see such a sight again.

The long journey was over. No longer would I have to hear that rasping command KURRA! (HEY YOU), Speedo, Speedo. Peace. My God, what a beautiful word that is. Please God, may the world enjoy it from now on. After a week of treatment, the next stop was Manila. During convalescence there we had a visit from Lady Mountbatten. From Manila across the Pacific to San Francisco. Sailing under the Golden Gate bridge I witnessed a happy sight. The bridge was lined with people calling out a welcome. Another week of care before boarding the train, and in First class luxury, over the Rockies, and with many stops, where the Americans made us feel so welcome. The kindness was, to say the least, touching. In New York we boarded the Queen Mary, which took us at great speed to Southampton. Home at last, after a journey that took me, in a tortuous fashion at times, round the world.

I received a letter from my eldest brother while in San Francisco, to inform me that our parents had died not long after they got the news of my being reported missing. A kind letter that, which gave me time to get over the shock to some extent, before finally arriving home.

After a happy meeting with family and friends at the Sunderland station, my brother George drove me home to where I had left five years ago. George was now living there temporarily because his home had been destroyed by a bomb.

I began adjusting to life. I remember walking through the park to the town centre. From a vantage point in the park I surveyed the scene, looking down the main street – Town Hall on the left, with its magnificent clock and tower – the Museum and Gallery. All as I had pictured so often in my mind. Still there, to be enjoyed. I just stood there and absorbed the scene. Then round to St George’s church, which played such an important part in my young life. Sitting in a pew that I had shared with mates, drinking in the atmosphere, and thinking of those school friends that did not come back.

Olga and Les Sinclair, my closest friends, were now married and living at Hooton in the Wirral, with their two baby sons. They both made me so welcome, as I have mentioned earlier.

Stephen Stark, another close friend, was living in Bolden, a small village north of Sunderland. My health was much improved by now and as recorded, started playing tennis during the glorious spring weather.

Then in June I departed on the liner Orbita, for Australia. Still a serving soldier, because the army are obliged to send you to your next-of-kin, my sister being the eldest in the family, was my next-of-kin. My three brothers still in England were not keen on this move, but I said that I was under no obligation to stay in Australia, but that here was the chance to see my sister and her husband and daughter June, who was now a medical student at Sydney University.

Now I live in Canberra with my wife, Ruth. Our son, William. is living in Sydney with his wife, Peta. Together they have produced the dearest grandchild (Stephanie, now 4‑5 years old) that any grandparent could wish for. This is peace indeed. I continue to count my blessings daily, hourly, and even every minute of the day. The neighbourhood we live in is quiet, and we are surrounded by friends.

When all those school friends mentioned earlier were children, we engaged in all the activities of childhood that delight the participants and grown-ups alike.

When Ruth and I and William went back to visit the neighbourhood in Sunderland and saw the house where the family were all born, and the other in the next street where we lived from 1927 until the war broke out, I recalled the games played with such joy in the streets and the adventures on such places as Tustall Hill and Rocky Hill next to it. Climbing Rocky Hill was to us as daring as the mountaineers climbing Everest. Then later, riding our pushbikes through the forest nearby with skill and daring. All this contributed to our health and strength, and I’m sure helped greatly in surviving what was to come.

It is worth noting that all these activities, and the joy they produced was done with the minimum of expense. Small additions were appreciated. To give but one example:‑ The school cricket team had only three bats and two pads for the whole team. You wore the pad on either the right or left leg, depending on whether you batted left or right hand. The wicket keeper wore both pads when we were fielding. When we won the Swan Cup (a competition where the school south of the river came to top of the Division, they played the corresponding school team north of the river), the game was recorded in the local press – “The Sunderland Echo”. Ruth unearthed this copy in the Sunderland Library, with the help of William, and had the page photocopied. There is a photograph of both teams and one of the two opening batsmen of the opposing side walking out to the wicket, with one pad only, as described above.

I never stop counting my blessings, especially as a parent watching William playing in the neighbourhood with his mates. (Most of them still see one another regularly to this day, and still enjoy each other’s company.) They played cricket and football exactly as we had done. And now, to all our joy, Stephanie, our Granddaughter, at four and a half years old, is doing it all over again.

Link to Fukuoka Camp 17 Roster

http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/fukuoka/Fuku_17/fuku_17_brit_roster.html

Sunderland Echo 1943

In Martin Place Sydney with Alf Wilkinson 1946.